- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

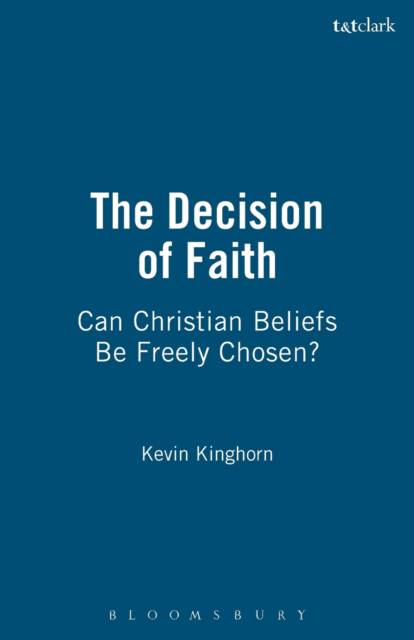

Christian theologians have historically described a 'saving faith in God' as containing a fundamental element of 'belief'. However, philosophers present strong arguments exist that we are not capable of freely deciding which beliefs we will hold. Rather, we simply find ourselves believing things as the evidence before us seems to dictate. So, if belief is indeed involuntary, and if certain beliefs are requisite for Christian faith, then how can the matter of one's salvation rest on whether one has freely put one's faith in God? After explaining this objection to the Christian affirmation that faith is a voluntary matter for which God will hold all people morally accountable, this study in philosophical theology explores how the Christian theist might respond to this objection. Kevin Kinghorn uses experimental studies within the psychological literature on self-deception to make sense of the Christian idea of 'spiritual blindness'; and argues that whether or not a person wilfully contributes to self-deception will hinge on decisions he or she makes either to embrace or avoid the truth as he or she sees it. Kinghorn then attempts to show that decisions of this type - more specifically, decisions to embrace or avoid the truth about God, wherever the truth lies - are ultimately more fundamental to the kind of relationship with God commended by the Christian religion than is the question of what a person believes. Kinghorn's conclusion is that the Christian theist can indeed rebut the objection pending against him or her, but only if he or she adopts Kinghorn's own account of the nature of faith, which provides a sharper distinction between faith and belief than is generally found in accounts of faith within the Christian tradition.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 208

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780567030689

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/12/2005

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 137 mm x 213 mm

- Gewicht:

- 249 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.