- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

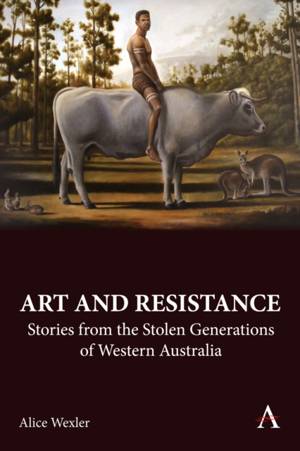

Art and Resistance

Stories from the Stolen Generations of Western Australia

Alice Wexler

Hardcover | Engels

€ 134,45

+ 268 punten

Omschrijving

The book traces the legacy of the child artists incarcerated at the Carrolup Native Settlement in the 1940s and 1950s. Many coincidences wereresponsible for bringing the new generation of Carrolup artworkto broader audiences, especially the (re)discovery of the lost body of Carrolup artwork in the United States in 2005.What might have remained a regional story has in past years become the locus of an international conversation, not only about the prodigious work of the children but also about colonialism, cultural genocide, repatriation and the protection of children's intellectual property.The conditions under which the artwork was made and its international response, invite a reexamination of how the production of hybrid forms of representation became both resistance and adaptation to colonization under totalizing conditions. Theauthor examines the children and their descendants within the politics, the artworld, the economy and the culture of Australia, past and present, and how they and their artwork were ontologically conceived in a colonialist country. Art historians and critics are not accustomed to writing about art made by schoolchildren, but they are not ordinary schoolchildren; they were survivors of the Stolen Generations who became known beyond the settlement because of fortuitous circumstances. This multidimensional story entails a confluence of priorities, values, worldviews, law, justice, time, and space. Both literal and symbolic meanings can be interpreted in the opening of a box of Indigenous children's art missing for 40 years, searched for by anthropologists with academic interests. One cannot help but notice the irony of the misplacement of both the contents of the box and its owners and custodians--that the people whose legacy was embodied in those works had few options based on the law of the land from which they had historically been omitted. Aboriginal arts have proliferated in both remote and metropolitan locations. And yet their success is one of the great paradoxes in Australian visual arts. Indigenous art is viewed as central, significant, and even indispensable in Australian visual culture. Their position is reflected in government and private resources committed to Indigenous artists and their inclusion in the artworld. But while the artworks are centrally located in Australian cultural public practice, and their financial returns to the nation's economy are substantial, Indigenous people remain sidelined.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 250

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781839988363

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 6/02/2024

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 453 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 268 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.