- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

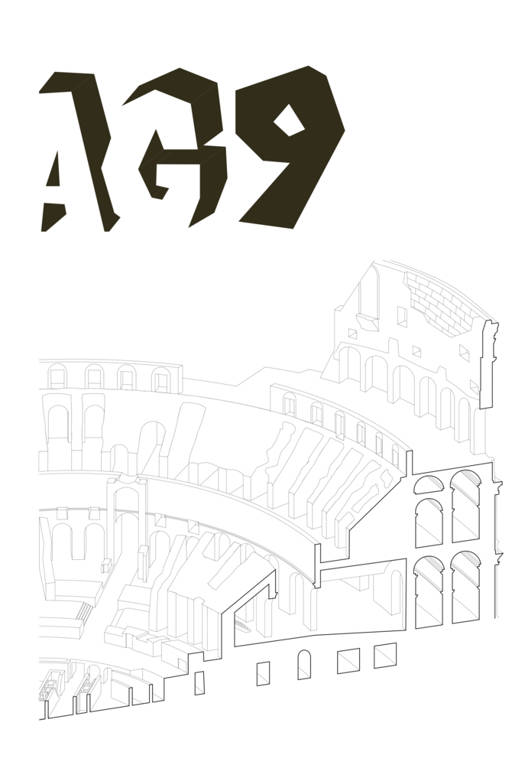

The beginnings of the description and recording of a specifically urban flora are generally located in the second half of the 19th century. Leo Hartley Grindon's "Manchester Flora" of 1859, which documents wild plants in the urban area and thus describes the city as an independent habitat in contrast to its surroundings, is considered groundbreaking in this respect.A fascinating precursor to early urban ecology can be found in the botanical studies of the Colosseum in Rome. The first flora of the Colosseum was written as early as 1643 by Domenico Panaroli, who as a physician was particularly interested in the unusual number of medicinal plants that grew on the ruins. Subsequently, the plant population of the building and its variety of microclimates - from the humid, shady hypogeum levels to the dry, exposed elevations - was recorded more and more systematically, so that today there is an exceptionally dense database on the vegetation of the Colosseum, which not only allows conclusions to be drawn about the (e.g. pastoral) use of the building or climatic changes, but also makes the interweaving of human cultural history with natural history tangible-the building is understood as an ecosystem. As plant biologist Giulia Caneva has shown in her analyses of historical records in her book Amphitheatrum Naturae (Electa, 2004), the increase in southern Mediterranean vegetation at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution is unmistakable evidence of an increasingly hotter and drier climate. The plants thus inform us about our own history and the Anthropocene era. The text is accompanied by photographs by Silvan Linden and drawings by Lukas Strasser.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Illustrator(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 64

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 9

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783943253658

- Afmetingen:

- 160 mm x 230 mm

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 23 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.