- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

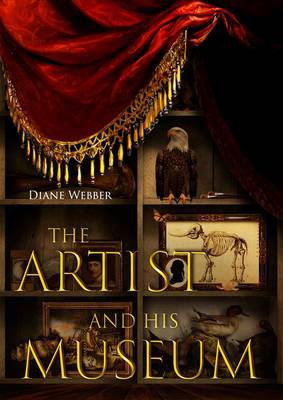

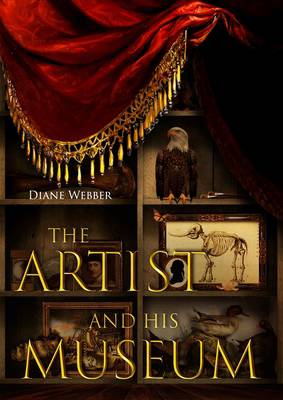

Charles Willson Peale's pioneering public museum combined science, art, and the emerging American identity.

Artist Charles Willson Peale was making detailed drawings of fossilized bones when a relative's off-hand comment sparked an idea in his mind--why not turn his art gallery into a museum of the natural world? People would come. People might even pay! His reputation as a portrait painter was growing, but so was the number of people living under his roof. Charles Willson Peale turned from his career as a successful portrait artist to become the proprietor of America's first public museum. Then (nearly) all of it disappeared, and (nearly) everyone forgot about it. What was Peale's Museum? And where did it go?

Unlike the wealthy person's "cabinet of curiosity" that came before, Charles wanted the museum to be organized by the latest ideas in scientific thinking. He believed useful knowledge should be available to the public, and hoped that his museum might offer Americans a sense of their emerging identity as citizens of a new nation. He dreamed that his museum would become a national, public institution, countering European views of American inferiority. Home to groundbreaking innovations in paleontology, taxidermy, and the role of scientific order, the museum survived yellow fever, multiple moves, and ongoing financial challenges before eventually closing. Today it's largely forgotten. Yet Peale's legacy lives on in the very idea of a museum as a space combining education and entertainment

Artist Charles Willson Peale was making detailed drawings of fossilized bones when a relative's off-hand comment sparked an idea in his mind--why not turn his art gallery into a museum of the natural world? People would come. People might even pay! His reputation as a portrait painter was growing, but so was the number of people living under his roof. Charles Willson Peale turned from his career as a successful portrait artist to become the proprietor of America's first public museum. Then (nearly) all of it disappeared, and (nearly) everyone forgot about it. What was Peale's Museum? And where did it go?

Unlike the wealthy person's "cabinet of curiosity" that came before, Charles wanted the museum to be organized by the latest ideas in scientific thinking. He believed useful knowledge should be available to the public, and hoped that his museum might offer Americans a sense of their emerging identity as citizens of a new nation. He dreamed that his museum would become a national, public institution, countering European views of American inferiority. Home to groundbreaking innovations in paleontology, taxidermy, and the role of scientific order, the museum survived yellow fever, multiple moves, and ongoing financial challenges before eventually closing. Today it's largely forgotten. Yet Peale's legacy lives on in the very idea of a museum as a space combining education and entertainment

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 128

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781955041645

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/06/2026

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 170 mm x 241 mm

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 55 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.