- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

€ 143,45

+ 286 punten

Omschrijving

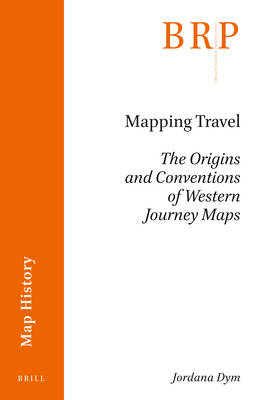

More often than not, readers of travel narratives can expect to find at least one map--if not several--showing, as English privateer William Dampier wrote, "the Course of the Voyage," that is, where the author-traveler went and, implicitly, a sense of what was seen and experienced. Dampier used a now-common cartographic strategy to tell the story from beginning to end as well as around significant places on the way by marking the journey with a 'pricked' line. Despite the lines' popularity and present ubiquity, the complex intellectual and material process of considering travel as a continuum rather than as a series of stops along the way and of plotting a journey onto a map have attracted relatively little academic attention. Drawing on a thousand years of European travel writing and map-making, Jordana Dym suggests that after centuries of text-based itineraries and on-the-spot directions guiding travelers and constituting their reports, maps in the fifteenth century emerged as tools for Europeans to support and report the results of land and sea travel. Called in subsequent centuries 'route maps, ' 'itinerary maps, ' and 'travel maps, ' often interchangeably, what Dym defines as journey maps added lines of travel to show where travelers had been. Sine their emergence, most have taken one of two forms: itinerary maps, which connected stages as points with a line, and route maps, which tracked unbroken lines between endpoints. In the seventeenth century, the conventions of journey mapping were codified and increasingly incorporated into travel writing and other genres that represented individual travel. With each succeeding generation, these linear journey maps have become increasingly common and complex, responding to changes in forms of transportation, such as air and motor car 'flight' and print technology, especially the advent of multi-color printing. This is their story.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 142

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789004499775

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 26/08/2021

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 155 mm x 236 mm

- Gewicht:

- 226 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 286 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.