- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

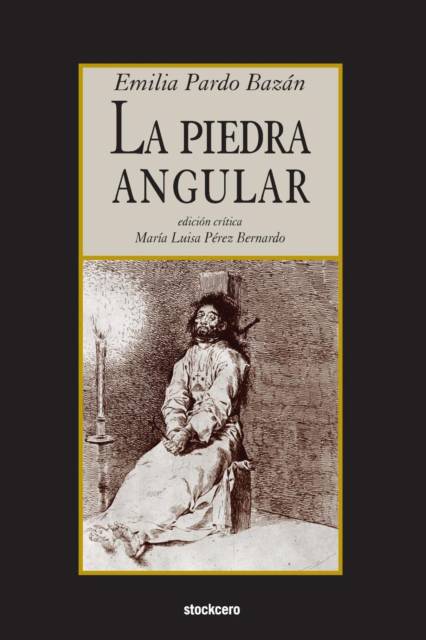

The plot of La piedra angular (1891) revolves around a crime: the brutal murder of a man by his wife and her lover. The novel is didactic, and attacks capital punishment, the "corner stone" of the title. On the issue of capital punishment, the author presents the reader with a variety of attitudes and ideologies. Emilia Pardo Bazán studies the executioner (Juan Rojo) and his family environment. In this way, La piedra angular analyzes the penal laws and criminal anthropological studies throughout its plot. The writer shows in her narrative the debate between legislators, philosophers, politicians and theologians over the validity of capital punishment. The author compares three characters, each personifying three distinct ideas of human justice in regards to the question of crime and the criminal in society. Through her novel, Bazán shows different points of views regarding the theme; clearly condemning the conservative attitude while showing the pros and cons of both sides. She also acknowledges the influence of Emilio Zola through his portrait of the sordid and brutal world of Marineda and the corrupting power of alcoholism. However, one should look less at the naturalistic school and more at the Russian writers that she studied and debated in her 1887 conferences at "Ateneo de Madrid" and in her work La revolución y la novela en Rusia (1887), where she praises Tolstoi, whom she regards over Zola.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 206

- Taal:

- Spaans

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781934768792

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/04/2015

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 308 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 91 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.