Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

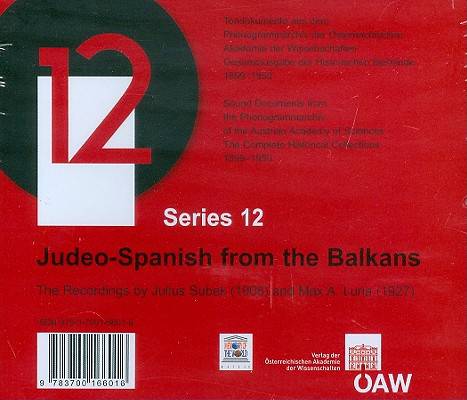

Judeo-Spanish from the Balkans LUISTERBOEK

The Recordings by Julius Subak (1908) and Max A. Luria (1927)

Christian Liebl

CD | Engels

€ 56,45

+ 112 punten

Omschrijving

During 1908/1909, Julius Subak (1872-1936), an Austrian Romance scholar, was entrusted by the Balkans Commission of the Imperial Academy of Sciences to record, both in writing and phonographically, the Judeo-Spanish of the Balkan Peninsula. He conducted his primarily linguistic investigation among the descendants of those Sephardim who - expelled from Spain in 1492 - had sought refuge in the Balkans, then part of the Ottoman Empire. The resulting 15 Phonogramme are said to be the first recordings of Judeo-Spanish (or Ladino) made for scholarly purposes. They contain chiefly poems and romances (the orally transmitted ballads from medieval Spain), but also songs and a passionate appeal to preserve the Judeo-Spanish language. Subak even succeeded in recording prominent representatives of Sarajevo's Sephardic community - such as Abraham A. Cappon, who is reciting from his own works. In 1927, the US-American Max A. Luria (1891-1966) undertook linguistic field research in Monastir (present-day Bitola, FYROM) as part of his doctoral dissertation. Equipped with an Archivphonograph, he made a total of 26 recordings which - featuring proverbs and dialogues, but above all numerous konsezas (folktales) - bring to life again this particularly conservative dialect of Judeo-Spanish. The contributions by Aldina Quintana Rodriguez, Edwin Seroussi and Rivka Havassy as well as Paloma Diaz-Mas highlight the importance of these unique sound documents, especially for Judeo-Spanish dialectology, but also for the study of Sephardic music and literature. Together with the transcriptions, they constitute a valuable supplement to the recorded witnesses of a once flourishing culture on the eve of cataclysmic changes.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 77

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783700166016

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/12/2009

- Uitvoering:

- CD

- Formaat:

- CD standaard audioformaat

- Gewicht:

- 198 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 112 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.