- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

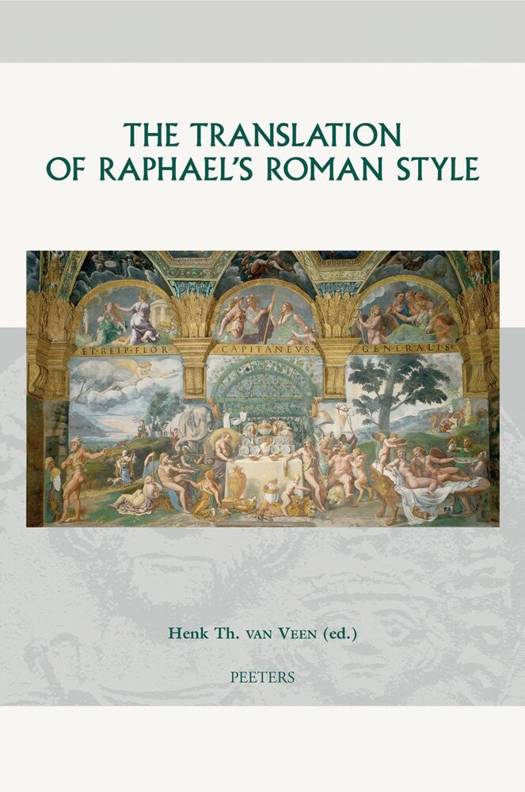

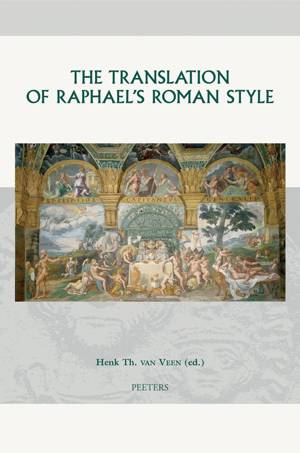

The papers assembled in this volume were read at the Cultural Crises in Art and Literature congress held at the University of Groningen (2002). Taking their inspiration from Marcia Hall's study, After Raphael. Painting in Central Italy in the Sixteenth Century (1999), the participants explored the mannerist style that Raphael developed in his last Roman years and that was promulgated throughout Italy by his main pupils. The question asked is how this new manner, which was based on the Roman imperial relief style, was reacted to at courts - Medici, Gonzaga, Farnese, Della Rovere - and in cities - Rome, Mantua, Pesaro, Florence - in Italy and at Fontainebleau. The papers show that the response to the new style was without exception a very conscious one. In Siena and Venice it was simply rejected, whereas in Pesaro, Mantua, Rome and Fontainebleau it was transformed or attempts were made even to surpass it. In other cases, Florence in particular, the answer to the new Raphaelesque style was found by proposing a conspicuously Michelangelesque one instead. In all these reactions, shaping or marking one's own identity appears to have been an important issue: for the artists of course, who spread the new style through Italy, but certainly also for the princely patrons who commissioned their works and even for the courts and cities as a whole. Seen as studies in artistic and cultural identity, the essays in this volume can rightly be considered a contribution to one of the most important recent developments in the historiography of Italian Renaissance art.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 138

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 22

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789042918559

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 6/04/2007

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 167 mm x 246 mm

- Gewicht:

- 467 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 90 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.