- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 15,02

+ 15 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

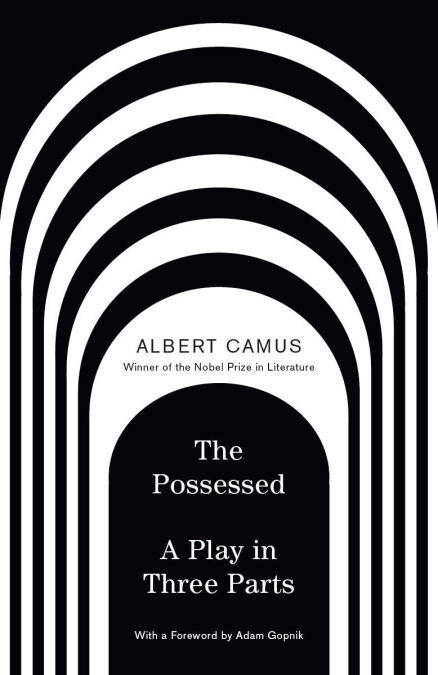

The Nobel Prize–winning author here adapts Dostoyevsky’s masterpiece for the stage—a rousing invective against nihilism that brings together two of the great literary minds of the last two centuries

When Albert Camus first read Dostoyevsky as a twenty-year-old philosophy student, it was a “soul-shaking experience.” The Possessed, in particular, had a profound effect on the young writer and thinker, who found in the novel an echo of his own disdain for the philosophy of nihilism and its potentially disastrous effects. “In many ways,” he writes in the foreword to the play, “I can claim that I grew up on it and took sustenance from it. For almost twenty years, in any event, I have visualized its characters on the stage.”

To complete this labor of love, Camus drew on hundreds of pages from Dostoyevsky’s The Notebooks for The Possessed, which document the Russian master’s torturous writing process, taking care all the while to preserve the “thread of suffering and affection that makes Dostoyevsky’s universe so close to each of us.” As a result, he breathed new life into the enigmatic Stavrogin, the gentle Shatov, and the God-haunted Kirilov, bringing us face to face with Dostoyevsky’s creations.

When it was finally performed, in 1959—with Camus himself directing—the play ran to four hours long and was an artistic and technical triumph, featuring thirty-three actors and seven sets. The last finished work before Camus’s death, The Possessed stands as an enduring literary statement about human existence in which the conscience of the twentieth century meets and defines in contemporary terms the conscience of the nineteenth century.

When Albert Camus first read Dostoyevsky as a twenty-year-old philosophy student, it was a “soul-shaking experience.” The Possessed, in particular, had a profound effect on the young writer and thinker, who found in the novel an echo of his own disdain for the philosophy of nihilism and its potentially disastrous effects. “In many ways,” he writes in the foreword to the play, “I can claim that I grew up on it and took sustenance from it. For almost twenty years, in any event, I have visualized its characters on the stage.”

To complete this labor of love, Camus drew on hundreds of pages from Dostoyevsky’s The Notebooks for The Possessed, which document the Russian master’s torturous writing process, taking care all the while to preserve the “thread of suffering and affection that makes Dostoyevsky’s universe so close to each of us.” As a result, he breathed new life into the enigmatic Stavrogin, the gentle Shatov, and the God-haunted Kirilov, bringing us face to face with Dostoyevsky’s creations.

When it was finally performed, in 1959—with Camus himself directing—the play ran to four hours long and was an artistic and technical triumph, featuring thirty-three actors and seven sets. The last finished work before Camus’s death, The Possessed stands as an enduring literary statement about human existence in which the conscience of the twentieth century meets and defines in contemporary terms the conscience of the nineteenth century.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Vertaler(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 224

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9798217008209

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 20/04/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Beveiligd met:

- Adobe DRM

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 15 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.