- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

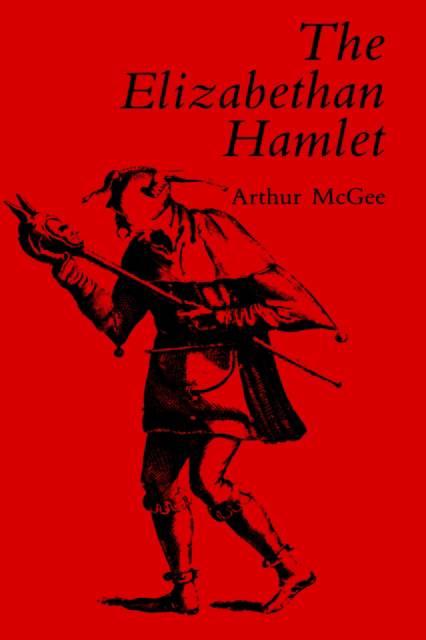

This original and provocative reinterpretation of Hamlet presents the play as the original audiences would have viewed it--a much bleaker, stronger, and more deeply religious play than it has usually been assumed to be. Arthur McGee draws a picture of a Devil-controlled Hamlet in the damnable Catholic court of Elsinore, and he shows that the evil natures of the Ghost and of Hamlet himself were understood and accepted by the Protestant audiences of the day.

Using material gleaned from an investigation of play-censorship, McGee offers a comprehensive discussion of the Ghost as Demon. He then moves to Hamlet, presenting him as satanic, damned as revenger in the tradition of the Jacobean revenge drama. There are, he shows, no good ghosts, and Purgatory, whence the Ghost came, was reviled in Protestant England. The Ghost's manipulation extends to Hamlet's fool/madman role, and Hamlet's soliloquy reveals the ambition, conscience, and suicidal despair that damn him. With this viewpoint, McGee is able to shed convincing new light on various aspects of the play. He effectively strips Ophelia and Laertes of their sentimentalized charm, making them instead chillingly convincing, and he works through the last act to show damnation everywhere. In an epilogue, he sums up the history of criticism of Hamlet, demonstrating the process by which the play gradually lost its Elizabethan bite. Appendixes develop aspects of Ophelia.

Using material gleaned from an investigation of play-censorship, McGee offers a comprehensive discussion of the Ghost as Demon. He then moves to Hamlet, presenting him as satanic, damned as revenger in the tradition of the Jacobean revenge drama. There are, he shows, no good ghosts, and Purgatory, whence the Ghost came, was reviled in Protestant England. The Ghost's manipulation extends to Hamlet's fool/madman role, and Hamlet's soliloquy reveals the ambition, conscience, and suicidal despair that damn him. With this viewpoint, McGee is able to shed convincing new light on various aspects of the play. He effectively strips Ophelia and Laertes of their sentimentalized charm, making them instead chillingly convincing, and he works through the last act to show damnation everywhere. In an epilogue, he sums up the history of criticism of Hamlet, demonstrating the process by which the play gradually lost its Elizabethan bite. Appendixes develop aspects of Ophelia.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 214

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780300039887

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 10/09/1987

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 163 mm x 241 mm

- Gewicht:

- 498 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 213 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.