- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

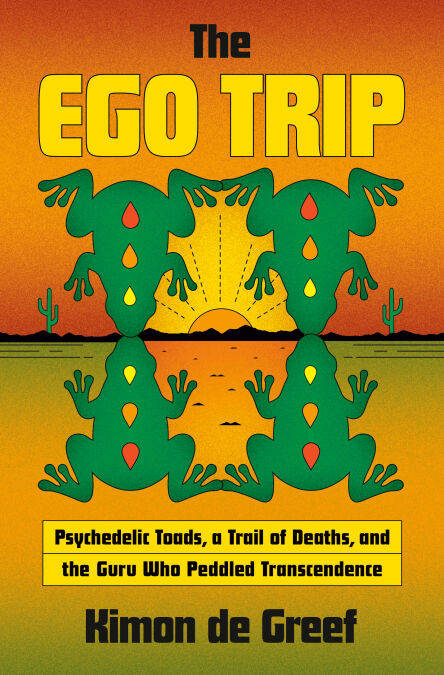

The Ego Trip E-BOOK

Psychedelic Toads, a Trail of Deaths, and the Guru Who Peddled Transcendence

Kimon de Greef

E-book | Engels

€ 17,34

+ 17 punten

Omschrijving

A charismatic doctor claimed to have rediscovered the ancestral roots of “toad medicine,” becoming the face of a global psychedelic movement. But in his wake, he left a trail of destruction that embodies the maladies of our spiritually desolate age.

In 2012, a Mexican doctor announced that he had revived a forgotten indigenous ritual: smoking the secretions of the Sonoran Desert toad, which releases a potent psychedelic substance known as “the God molecule.” The drug, which often induced states of ego death and the sensation of being directly connected with the divine, had remarkable effects on those suffering from PTSD, depression, and drug addiction. As the doctor’s fame grew, however, stories emerged of extreme dosing, abusive behavior, and even dramatic deaths.

In this gripping and deeply reported book, Kimon de Greef explores the promise and the peril of “toad medicine” and captures the defining tensions of this new era of psychedelics. As the notoriety of this powerful drug rose, psychonauts, spiritual seekers, and sufferers of innumerable conditions flocked to Sonora, giving rise to a bourgeoning economy of psychedelic tourism. Many of the Seri people, who had once lent their imprimatur to the doctor’s narrative of indigenous tradition, conspicuously avoided using the substance at all, and evidence of ancestral use appeared questionable. Impoverished toad collectors chased after the animals in drug cartel territory and risked their lives in the process. And pharmaceutical companies raced against one another to harness the therapeutic potential of the toad’s chemical wonders and develop a world-altering breakthrough in mental illness treatment—a drug that could rival Prozac in its impact on psychopharmacology.

Part true crime, part cult story, part cultural history, The Ego Trip is a chronicle of the rise and fall of a messianic figure, but it is also an investigation into a larger truth about our age of spiritual desolation. As this story forcefully demonstrates, no matter the lengths we go to in attaining a more cosmic understanding, we will always be firmly rooted in the real world, bound by our limitations and inescapably human.

In 2012, a Mexican doctor announced that he had revived a forgotten indigenous ritual: smoking the secretions of the Sonoran Desert toad, which releases a potent psychedelic substance known as “the God molecule.” The drug, which often induced states of ego death and the sensation of being directly connected with the divine, had remarkable effects on those suffering from PTSD, depression, and drug addiction. As the doctor’s fame grew, however, stories emerged of extreme dosing, abusive behavior, and even dramatic deaths.

In this gripping and deeply reported book, Kimon de Greef explores the promise and the peril of “toad medicine” and captures the defining tensions of this new era of psychedelics. As the notoriety of this powerful drug rose, psychonauts, spiritual seekers, and sufferers of innumerable conditions flocked to Sonora, giving rise to a bourgeoning economy of psychedelic tourism. Many of the Seri people, who had once lent their imprimatur to the doctor’s narrative of indigenous tradition, conspicuously avoided using the substance at all, and evidence of ancestral use appeared questionable. Impoverished toad collectors chased after the animals in drug cartel territory and risked their lives in the process. And pharmaceutical companies raced against one another to harness the therapeutic potential of the toad’s chemical wonders and develop a world-altering breakthrough in mental illness treatment—a drug that could rival Prozac in its impact on psychopharmacology.

Part true crime, part cult story, part cultural history, The Ego Trip is a chronicle of the rise and fall of a messianic figure, but it is also an investigation into a larger truth about our age of spiritual desolation. As this story forcefully demonstrates, no matter the lengths we go to in attaining a more cosmic understanding, we will always be firmly rooted in the real world, bound by our limitations and inescapably human.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 336

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780385550239

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 3/08/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Beveiligd met:

- Adobe DRM

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 17 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.