- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

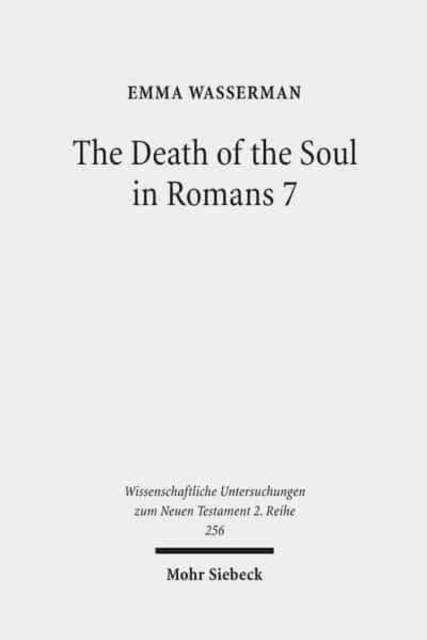

The Death of the Soul in Romans 7

Sin, Death, and the Law in Light of Hellenistic Moral Psychology

Emma Wasserman

€ 82,45

+ 164 punten

Omschrijving

The monologue of Romans 7 has proved central to the Christian West, where interpreters such as Augustine and Martin Luther have made the text into a paradigm for the plight of mankind, torn between the demands of God's goodness and its own sinful nature. Emma Wasserman argues that the monologue can be better contextualized within certain intellectual discourses alive in Paul's day. In light of certain Platonic traditions about the soul, the monologue emerges as the voice of reason or mind describing its defeat at the hands of passions and desires represented as sin. Especially as developed by Philo of Alexandria, Platonic traditions of representing extreme cases of immorality account for a number of difficult features of the text. Such traditions can account for the metaphors of enslavement, imprisonment, warfare, and death; the representation of the passions as sin and the association with the body, members, and flesh; the Platonic language about mind and the speaker's role in reasoning, reflecting, and judging; the problem of the law in the first part of the monologue (verses 7-13) and the plight of self-contradiction in the second (14-25). The reading thus finds that the speaker is reason or mind, recounting its discovery that it cannot put any of its good judgments into action because of the dominance of the passions.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 171

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783161496127

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 31/12/2008

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 153 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 290 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 164 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.