- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

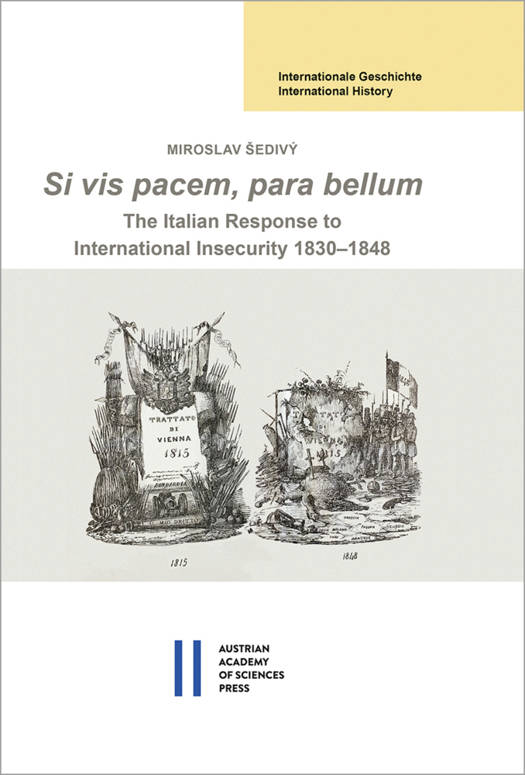

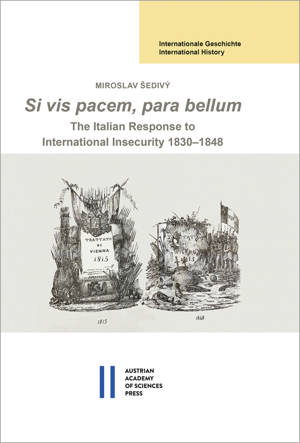

Si VIS Pacem, Para Bellum

The Italian Response to International Insecurity 1830-1848

Miroslav Sedivy

€ 149,45

+ 298 punten

Omschrijving

It was not after 1848 but actually before this revolutionary year that Europe witnessed the abusive proceedings perpetrated by the great powers which undermined the functionality of the post-Napoleonic international order. Even worse, their abuse of power in European and overseas affairs provoked a feeling of mistrust, pessimism and fear and led to discussions about the disappearing justice from the world among a considerable number of Europeans. By the 1840s, under the influence of various crises and conflicts members of the educated middle and upper middle classes in particular changed the way they judged and approached issues of international politics, justice, security and nation building. This process was all the more important in Italy since the search for greater security against external threats became the driving force in the spread of the idea to unite her politically from the Alps to Sicily. This unity, along with well defensible frontiers, a strong army and navy and good material resources including colonial ones, was to ensure a more secure position within the system of European politics and thereby better prospects for a peaceful future according to the phrase Si vis pacem, para bellum. However, this power-oriented response to insecurity had devastating consequences for the generally shared desire to live in peace with other nations, represented by another aspiration deeply rooted in the national movement: to establish a better international order. To reveal this important process of pan-European dimension is the principal aim of this book, and the Italian arena of politics in 1830-1848 has been chosen to clarify this sea change in political behaviour.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 346

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 7

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783700187059

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 8/09/2021

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 176 mm x 246 mm

- Gewicht:

- 879 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 298 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.