- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

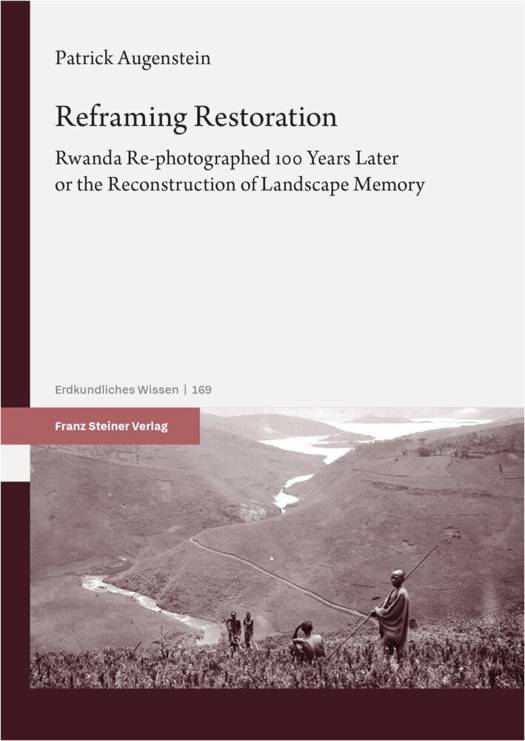

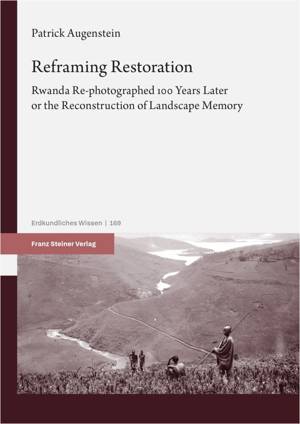

Reframing Restoration

Rwanda Re-Photographed 100 Years Later or the Reconstruction of Landscape Memory

Patrick Augenstein

€ 69,45

+ 138 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

Almost universally, the loss of forest cover in Rwanda, Africa's most densely populated country, has been explained by population growth. Imaginations of vast forest landscapes prior to colonialism shape today's ecological restoration policies, aiming at 30 % forest cover countrywide. Newly re-discovered historical photographs from 1892 to 1916 challenge this conventional account. The course of events over the past 100 years might not be consistent with the narrative of deforestation, where old-growth forests progressively disappeared as human populations increased. As systematically re-photographed viewsheds across Rwanda show, the contrary seems likely: increasing numbers of people in the 20th century appear to coincide with an increase in overall standing biomass. Deforestation has been less drastic than previously thought, primarily because of extensive landscape management by fire for pastoralism and subsistence agriculture by local peoples prior to colonial activity. In fact, the overall standing biomass has increased in all re-photographed viewsheds. Linking repeat photography, ecological restoration, and political ecology allow for a critical engagement with long-standing narratives on landscape change and restoration goals and practices.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 340

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 169

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783515129473

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/06/2025

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 170 mm x 239 mm

- Gewicht:

- 544 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 138 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.