- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 203,95

+ 407 punten

Uitvoering

Omschrijving

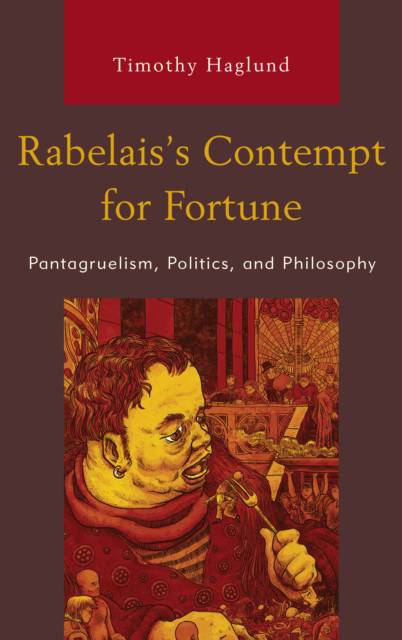

Francois Rabelais wrote Gargantua and Pantagruel at the height of the Renaissance, when top-caliber thinkers aimed to unite the best of freshly rediscovered ancient Greco-Roman theory and practice and transform politics. Through his work, Rabelais offers his unique understanding of ancient philosophy and political thought. This book considers the role of fortune as the key to understanding Rabelais, much in the manner of contemporaries such as Machiavelli. The two could not be more different, however. Throughout his writings, Rabelais attempts to restore respect for the goddess Fortuna through a cheerful restatement of the case for the sober classical attitude toward future things. As Rabelais's headstrong character Panurge seeks counsel regarding his marriage prospects, various authorities repeatedly warn him that cuckoldry and spousal abuse await. Panurge looks foolhardy during these admonitions. Far from affirming Machiavelli's instruction, given in chapter 25 of The Prince, to beat fortune like a woman, Rabelais dramatizes Panurge learning that his future femme may beat him. Through this dramatization, Panurge begins to hear the merits of viewing fortune as an intractable part of life that must be shouldered with the proper inner disposition rather than as an object susceptible of human conquest.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 178

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781498575454

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 19/11/2018

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 160 mm x 231 mm

- Gewicht:

- 408 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 407 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.