- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

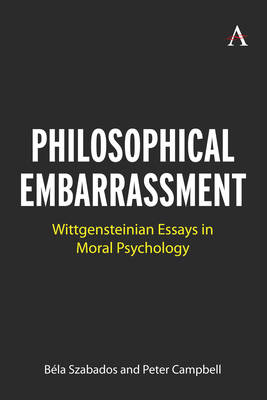

Philosophical Embarrassment

Wittgensteinian Essays in Moral Psychology

Béla Szabados, Peter CampbellOmschrijving

Examines episodes of philosophical embarrassment, highlighting how Hume, Wittgenstein, and others grappled with critiques that undermined philosophy's foundations, leading to redefinitions of its aims and cautionary responses to scientism and self-deception

This book consists of diverse essays held together by the thread of embarrassment that runs through them. Sometimes, embarrassment is front and center as when we discuss its conceptual features; at other times, its presence is oblique, as when we take a closer look at Rousseau's existential outrage at the very idea of a culture of embarrassment; or when we look at Darwin's theory and George Eliot's critique of it. We unearth deeply buried embarrassments in the history of philosophy treating them as useful entry points into the major figures from an unusual if not idiosyncratic angle. All this raises a somewhat different but important line of enquiry, one that is meta-philosophical. Hume and Wittgenstein are our prime examples of philosophers who are aware that they and their subject have undone themselves and thus have been thoroughly embarrassed. What are the upshots, they ask, for philosophers and their subject? Perhaps this issue is the answer to Rousseau's tantrums: embarrassment is useful. Throughout the book, we have many things to say about its uses and its abuses. One question this raises for us is how to proceed in philosophy with equipment that tends to run off the rails with considerable regularity. Do we proceed with all modesty, alive to these facts about us and ready to be embarrassed the next time our reach exceeds our grasp? Or do we, as the early Wittgenstein, the Vienna Circle, and Quine seem to have done, radically revise key elements of the philosophical project--the pursuit of truth and objectivity in all matters, for example--in an attempt to avoid future embarrassments? If you narrow your subject, and if you are competent in that narrowness, you can avoid embarrassment and achieve your modest goals. Such a course is in keeping with the approach of modern philosophy, since it has taken science as a model of sorts. However, when science exceeds its competence, claiming it can solve any and every problem, it loses its experimental modesty, and we no longer have science but scientism. It should come as no surprise, then, that one of our essays is a set of reflections on Wittgenstein's cautionary remarks about the embarrassments of scientism and his warnings about the related inclination to self-deception. A definition, Kant remarked, should come toward the end rather than at the beginning of an investigation; hence, in the final essay, we provide a perspicuous overview of embarrassment.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 200

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 1

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781839997662

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 12/05/2026

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Gewicht:

- 453 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.