- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

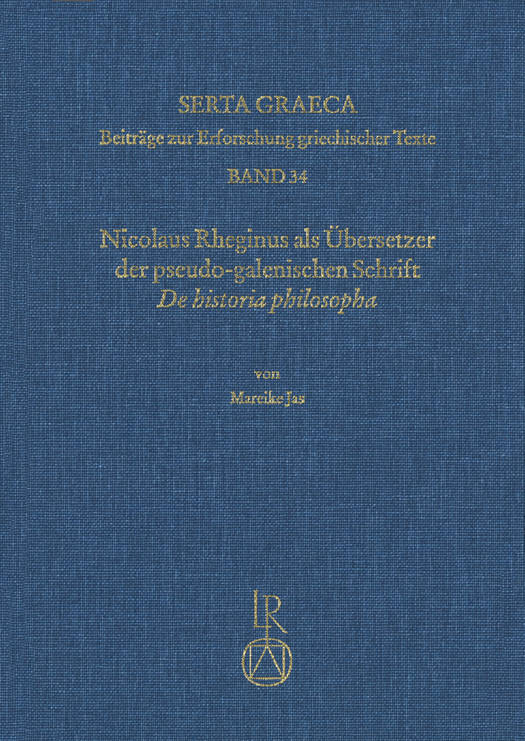

Nicolaus Rheginus ALS Ubersetzer Der Pseudo-Galenischen Schrift de Historia Philosopha

Ein Beitrag Zur Lateinischen Uberlieferung Des Corpus Galenicum

Mareike Jas

€ 131,95

+ 263 punten

Omschrijving

The pseudo-Galenic text De historia philosopha is a particularly useful one in that it can help us develop an idea about the quality of the Greek manuscripts Nicolaus Rheginus used for his translation of Galenic and pseudo-Galenic texts. This is because Nicolaus' translation can be compared not only with the extant Greek manuscripts of the Historia philosopha in general but also with the Placita philosophorum by pseudo-Plutarch in particular and the extant excerpts of the latter, for example those in Eusebius' Praeparatio Evangelica. For as an epitome of the Placita philosophorum the Historia philosopha belongs to the doxographical tradition as well as Stobaeus' Eclogae physicae. The Placita philosophorum and the Eclogae physicae decline to the lost doxographical text Περὶ τῶν ἀρεσκόντων τοῖςφιλοσόφ οις φυσικῶν δογμάτων ἐπιτομῆς by Aetius. The affiliation of the Historia philosopha to this doxographical tradition therefore provides an independent and objective instrument of control in the assessment of readings preserved in Nicolaus' translation. For all readings can be compared with the Greek text of the Placita philosophorum as transmitted by the extant byzantine manuscripts, by one of the excerpts, for example transmitted in Eusebius' Praeparatio evangelica, or with Stobaeus? Eclogae physicae. The doxographical tradition is therefore an independent and objective instrument of control, because contamination of Nicolaus' translation with one of these texts can be excluded. There is no evidence in Nicolaus' translation that he used a manuscript that contained one of the other texts. As well as Hieronymus Surianus, who printed Nicolaus' translation in 1502 and which is the only extant source for his translation, given that no Latin manuscript of the Historia philosopha has been transmitted. A contribution to this independent tradition is given to the fact that the Placita philosophorum has been passed down in the text corpus of Plutarch, while the Historia philosopha as an epitome of this text has been passed down in the Galenic text corpus. This prevented the knowledge about the relationship between those two texts until the printed Greek edition of the Historia philosopha from 1525, where first signs about the knowledge about this relationship are obvious. The correlation of the Historia philosopha, the Placita, the Praeparatio evangelica and the Eclogae physicae was not known until the 16th century as well.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 512

- Taal:

- Duits

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 34

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9783954901951

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 21/09/2018

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Afmetingen:

- 170 mm x 240 mm

- Gewicht:

- 1006 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 263 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.