- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

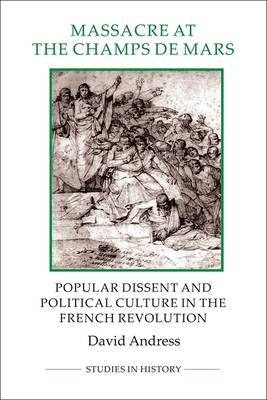

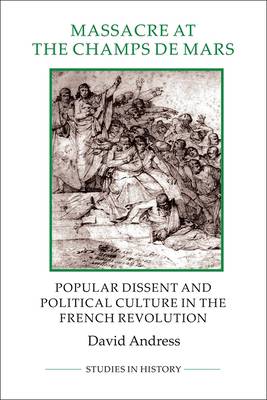

Massacre at the Champ de Mars

Popular Dissent and Political Culture in the French Revolution

David Andress

€ 59,95

+ 119 punten

Omschrijving

On 17 July 1791 the revolutionary National Guard of Paris opened fire on a crowd of protesters, citizens who saw themselves as patriots, trying to save France from a traitor king. To the National Guard and their political superiors, however, the protesters were the dregs of the people, brigands paid by counter-revolutionary aristocrats. Politicians and journalists rallied to an account of this event in which the National Guard were the patriots, and their action a heroic defence of the fledgling Constitution. Under the Jacobin Republic of 1793, however, this 'massacre' would be regarded as a high crime, a moment of clarity in which the treasonous designs of a corrupt elite were exposed. But political clarity is the last attribute that emerges from a detailed study of the events of July 1791 and their antecedents. Paris in early 1791 was feverish with political involvement. Ordinary people expressed violent opinions on the street corners, journalists published wild rumours one day and denounced scaremongering the next, political clubs grew like mushrooms and advocated the most radical solutions to political deadlock and crisis. In such an atmosphere, what did it mean to be 'one of the people'? Where were boundaries to be drawn around the national community? How could one identify threatening outsiders? What should be done about them? This book explores how Parisians of all classes sought to answer such questions, and why it was that the answers they found drove 'patriots' to confront each other on the Champ de Mars.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 256

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 17

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781843838425

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 18/07/2013

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 156 mm x 234 mm

- Gewicht:

- 362 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 119 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.