- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

Omschrijving

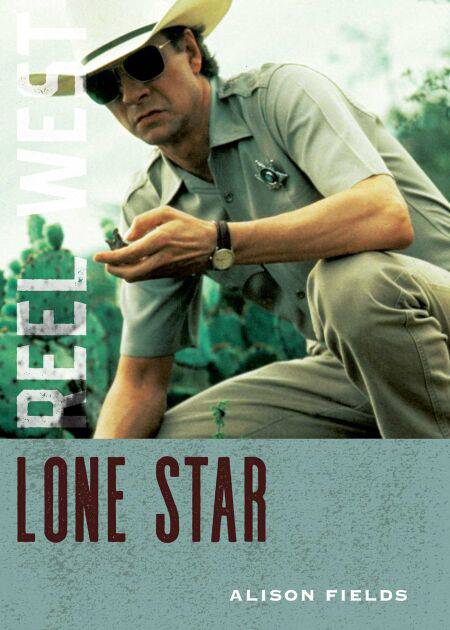

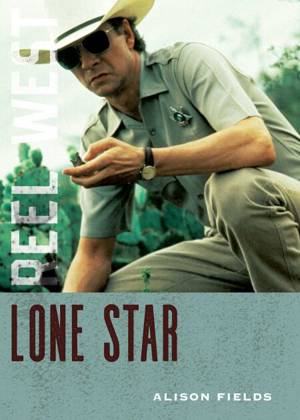

A deft history and analysis of John Sayles’ 1996 cinematic masterpiece. Alison Fields places Lone Star in a western film framework and emphasizes Lone Star's ability to highlight the conflicts between socially entrenched borderlands history and its multifaceted reality.

Filmmaker John Sayles has been a key voice in independent cinema since the 1970s, interrogating American legends by retelling stories about class, race, labor, sexuality, history, and violence.

Lone Star, released in 1996, was ahead of its time in exploring the prevailing legends of the Borderlands through the intersectionality of Black, Chicano, and women’s narratives. Set in the fictional small town of Frontera on the Texas/Mexico border, the film opens with the discovery of a decades-old skeleton on a rifle range—the remains of racist and corrupt former sheriff Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson). It had long been presumed that Wade was driven from town by Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey), who succeeded him for a long tenure as Frontera’s beloved sheriff. The discovery of Wade’s remains prompts current sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), who had always lived in his father’s shadow, to question Buddy’s legacy and his involvement in Wade’s death and to look to the testimonies of the poor, the dispossessed, and the overlookedthe very people the late Sheriff Wade had victimized.

In the first book-length examination of Lone Star, Fields situates the film firmly in the “new Western history” that has done so much to overturn the century-old Frontier Thesis.

Filmmaker John Sayles has been a key voice in independent cinema since the 1970s, interrogating American legends by retelling stories about class, race, labor, sexuality, history, and violence.

Lone Star, released in 1996, was ahead of its time in exploring the prevailing legends of the Borderlands through the intersectionality of Black, Chicano, and women’s narratives. Set in the fictional small town of Frontera on the Texas/Mexico border, the film opens with the discovery of a decades-old skeleton on a rifle range—the remains of racist and corrupt former sheriff Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson). It had long been presumed that Wade was driven from town by Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey), who succeeded him for a long tenure as Frontera’s beloved sheriff. The discovery of Wade’s remains prompts current sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), who had always lived in his father’s shadow, to question Buddy’s legacy and his involvement in Wade’s death and to look to the testimonies of the poor, the dispossessed, and the overlookedthe very people the late Sheriff Wade had victimized.

In the first book-length examination of Lone Star, Fields situates the film firmly in the “new Western history” that has done so much to overturn the century-old Frontier Thesis.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 168

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9780826369406

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 6/04/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Beveiligd met:

- Adobe DRM

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 11 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.