- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

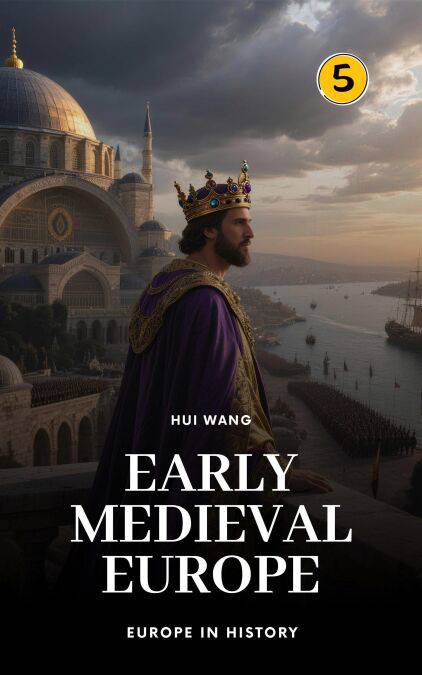

Early Medieval Europe: Europe in History, PART ONE, is the book I set out to write when I first realized just how bewildering the years after Rome really are. This narrative begins in the wake of the fall of the Western Roman Empire (commonly dated to 476 CE) and follows a long, uneasy transition rather than a neat, instantaneous break. Tracing the older biblical traditions—from the figure of Moses in the religious imagination—to the arrival of Jesus and the slow, often violent spread of Christianity, I map how lingering Roman power, emerging religious ideas, and fragile institutions collided and reshaped a continent. Europe did not suddenly wake up medieval; it stumbled there, step by step, under the twin pressures of conviction and calculation, of belief and bare survival.

At the center of the story stand figures such as Constantine the Great, whose decisions altered both the map of empire and the map of faith. He legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan (313) and convened the Council of Nicaea in 325, moments that pulled theology into the bloodstream of politics. I guide readers through Nicaea, the rise and contestation of Christian doctrine, and the influence of currents like Neoplatonism on early Christian thinkers. Arius and Alexander were not dusty theologians tucked away in cloisters—their quarrel over the nature of Christ split cities, inflamed popular loyalties, and forced emperors to pick sides. Councils became arenas of power where theological verdicts could help crown a ruler or topple one.

As the empire strained, emperors fought to hold the reins. The Battle of Adrianople in 378 cracked the Roman military façade and reshaped politics; it helped usher Theodosius into power and set the stage for a new religious order when his reign hardened Nicene Christianity into imperial policy. The fall of John Chrysostom—forced from the patriarchate and exiled after clashing with court power—made plain how dangerous it was to speak truth from the pulpit when it challenged the throne. Meanwhile theological storms—arguments over Nestorianism and debates that would culminate at Council of Ephesus (431) and later the Council of Chalcedon (451)—pulled the empire into doctrinal combat. Chalcedon proclaimed a form of unity, but the peace it offered was brittle, and religious dispute kept the seams of empire taut.

Then the crisis broke into the open. The rise of the Goths, Alaric's shocking sack of Rome in 410, and the ripple of panic that spread across the Mediterranean marked a new phase of decline. Gaiseric's seizure of Roman Africa and the loss of Carthage in 439 stripped the West of vital grain and revenue, while Attila's Huns stormed across Gaul and into Italy, proving how exposed the western provinces had become. In this collapsing world, Anthemius—installed as Western emperor in the late 460s with Eastern backing—stands out as Rome's last serious gamble: an effort to stitch the old order back together even as the threads were already slipping through history's fingers.

The final chapters look beyond collapse. From Justinian and Theodora's bold programs of law, rebuilding, and reconquest to the wrenching debates over icons, the doctrinal battles that rent churches, and the slow road to the Macedonian Renaissance, I follow how the Eastern Empire adapted and survived. The Roman Empire did not simply vanish—it continued in the east and, over centuries, evolved into what historians call the Byzantine Empire, an eastern Roman state reshaped by Greek language, Christian faith, and administrative reinvention. The world after Rome was forged by faith and violence as much as by compromise and creative reinvention.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789190150207

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 4/02/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.