Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Bedankt voor het vertrouwen het afgelopen jaar! Om jou te bedanken bieden we GRATIS verzending (in België) aan op alles gedurende de hele maand januari.

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- In januari gratis thuislevering in België

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

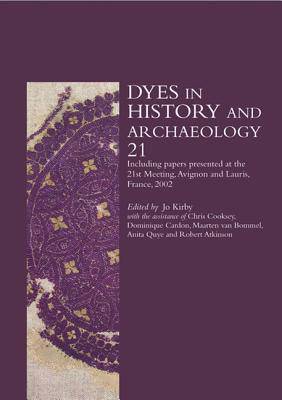

Dyes in History and Archaeology 21

Paperback | Engels

€ 129,95

+ 259 punten

Omschrijving

The trade in dyestuffs has played an important role in the economic history of many nations. In medieval Europe this is demonstrated by the important place held by woad in the economy of many countries, but while the woad industry of Toulouse or Erfurt is quite well known, that of Catalonia and Roussillon is rather less familiar. Other aspects of medieval woad dyeing are equally interesting: it is known that the vat contains indigo-reducing bacteria, but how do these bacteria interact with the indigo to make the process work? In fact, identifying the dye present in fragments of aged or degraded textile or in a tiny pigment sample is only half the battle: we are still left wondering how the effects revealed by the analysis were achieved. Thus, madder was widely used in Roman and Coptic Egypt, but which madder? How do the red pigments used to paint the sumptuous glazes on 15th- or 16th-century European paintings relate to the textiles dyed with the same dyes? Some classes of works of art present particular problems because no sample may be taken or because the materials used in the construction of the object are poorly understood or particularly intractable. Many Japanese objects of cultural heritage can only be studied by non-invasive methods, but sometimes this study can be greatly assisted by even a limited amount of analysis, as demonstrated by the discussion of braids used in Japanese armour. The organic pigments used in illuminated manuscripts present a similar problem as they are often difficult to identify by non-invasive methods. Some, such as the anthocyanin blues and exotic dragonsblood, are also not particularly well characterised while others, such as the expensive shellfish purple also found on Roman and Coptic textiles, are tantalisingly rare. These topics are among those discussed in the papers presented at the 21st Meeting of Dyes in History and Archaeology, held in Avignon in 2002, together with discussions on a range of topics from theoretical studies of alizarin complexes to the use of logwood as a biological stain and the use of dyes in West Africa and 18th-century Poland.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 246

- Taal:

- Engels

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9781904982074

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/12/2008

- Uitvoering:

- Paperback

- Formaat:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Afmetingen:

- 170 mm x 241 mm

- Gewicht:

- 657 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 259 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.