- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Zoeken

€ 159,00

+ 318 punten

Omschrijving

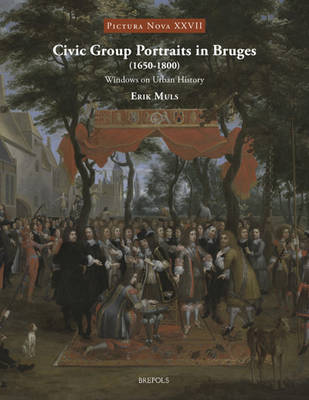

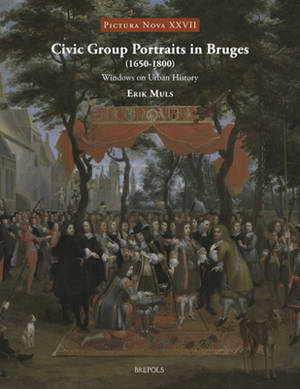

The patrons of civic group portraits were corporate organisations such as confraternities, craft and militia guilds, charitable institutions, and administrative bodies. Up until now, the painted civic group has been primarily seen as a product of the Dutch Republic. While the genre may have been exceptionally important in the Northern Low Countries, the present study shows that such paintings were also fundamental in the South, with Bruges playing a central role. From the late fifteenth century until 1800, both the urban elite and the artisan classes of Bruges commissioned institutional group portraits, and the forms that those artworks took responded to local conditions and needs. The patrons' self-representation in these works was meant to emphasize the internal cohesion and solidarity within their group, and to reinforce that group's social status in the urban community. In looking carefully at these contexts, this research project has provided new interpretations for civic group portraits and has demonstrated their richness as both cultural heritage and historical sources. The Bruges works, however, represent just a portion of those produced in the Southern Netherlands during the early modern era. The author provides an updated inventory of 190 civic group portraits that he has been able to trace for the Southern Netherlands. All of these works, moreover, need to be set in a broader European context, as civic group portraits are also recorded in Venice, Paris, and England, and were likely produced elsewhere as well. Future researchers will be able to expand our understanding of the genre as a European phenomenon, continuing to reveal the significance of these remarkable artworks and use them to gain deeper insights into the past.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Aantal bladzijden:

- 465

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

- Reeksnummer:

- nr. 27

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9782503618395

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 1/12/2025

- Uitvoering:

- Hardcover

- Formaat:

- Genaaid

- Gewicht:

- 984 g

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

+ 318 punten op je klantenkaart van Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.