- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

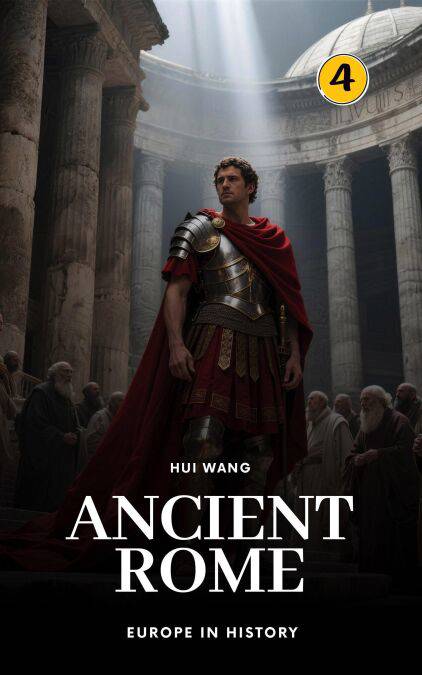

Ancient Rome: Europe in History, PART TWO, is the book I wish I'd had when I first tried to make sense of Rome's long slide from republic to empire. I start with Gaius Marius — the reformer whose changes to recruitment and the structure of the legions quietly altered the balance of power in Rome — and then press on to the hard question of why the Republic broke down at all.

From there, Sulla steps onto the stage, a living example of how violence and the pursuit of personal power became routine tools of Roman politics long before Caesar ever crossed the Rubicon. As the story unfolds I lead you into the world of Pompey and Crassus and a Senate that clung to the illusion of control even as it was losing its grip.

The First Triumvirate — Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus — looks formidable from the outside, but it is built on rivalry, mutual suspicion, and fragile convenience. That tension ultimately explodes into open civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey, culminating in Caesar's victory and the effective end of the old Republic. His assassination closes one chapter of Roman history, but it precipitates a far darker and more chaotic one.

The next act belongs to the Second Triumvirate — the brutal rivalry that boiled down to Octavian and Mark Antony. I follow how Octavian outmaneuvered every rival, co-opted institutions and loyalties, and built an imperial machine step by patient step — all while refusing the title of king. He styled himself Princeps and, when he accepted the honorific Augustus in 27 BC, transformed the republic's forms into a working mask for a new, hidden monarchy.

Under Augustus, Rome learned to live with that disguise: dynastic maneuvering, emperors who ruled from behind the language of the old republic, and an official reverence that could slide into emperor-worship. From there, the story moves through the empire's high water and its long, slow erosion. I examine the rise of the imperial cult and the long calm under the Five Good Emperors (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius), then the sharp turn under Caracalla and into the era of the barracks emperors — the soldier-kings who made the purple a prize seized by the army. Stability gave way to military politics, short reigns, and an empire always on edge.

The final chapters follow Rome through its last great experiments. Diocletian's Tetrarchy — a divided rule of two Augusti and two Caesars — was a desperate bid to save the empire with rigid structure, sweeping administrative and fiscal reforms, and an iron discipline meant to end the chaos of the third-century crisis. Constantine reshaped the map again: he re-founded Byzantium as Constantinople in 330 and, with the 313 Edict of Milan (issued alongside Licinius), put Christianity on a new footing by legalizing it and ending imperial persecution. That shift set Christianity on a path to imperial favor — though it would only become the empire's official religion later, under Theodosius. I close by confronting the biggest question of all: why did the Western Roman Empire collapse while the East endured?

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789190150184

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 2/02/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.