- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

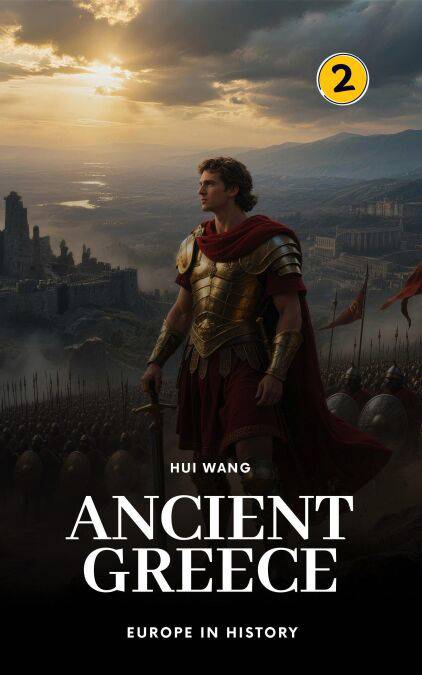

Ancient Greece: Europe in History, PART TWO, is my attempt to tell the Greek story the way it actually felt to live it—tense, unstable, and full of agonizing choices. I open the book with two competing roads to power, Athens and Sparta, and trace how their very different ideas about freedom, discipline, and leadership pushed the Greek world toward confrontation. What begins as cooperation—alliances and shared purpose—slowly hardens into rivalry, and then into something far more destructive.

The rise of Athens is narrated through real people, not abstractions. Men like Cimon and Pericles make visible how alliance politics frayed and how Athens drifted from leadership into outright empire. Cimon, the earlier generation, pushed Athenian influence at sea while favoring conciliation with Sparta; Pericles, later, presided over the city's golden age and its imperial consolidation and, during the great war, argued for a strategy that relied on the navy, the city's walls, and its resources rather than reckless land engagements. The earlier conflict often called the First Peloponnesian War (c. 460–445 BCE) and the later, much larger struggle commonly known simply as the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) — sometimes called the Second Peloponnesian War in periodized accounts — together reveal a city trying to rule others while convincing itself it was still free. In that struggle, ships, money, speeches, and civic pride mattered as much—sometimes more—as hoplites on the battlefield.

As the war drags on, individuals begin to bend events in dangerous, unexpected ways. Episodes at Pylos and the daring rise of Brasidas expose how fragile power really is, how a single battle or charismatic commander can tilt the balance. Then comes Alcibiades—brilliant, extravagant, and corrosive—whose personal brilliance accelerates political and military chaos. That chaos deepens with the opportunism of Theramenes, the oligarchic coup of the Four Hundred, and the uneasy, short-lived government of the Five Thousand. The brief, brutal reign of the Thirty Tyrants and the trial and execution of Socrates become the shattering moments for Athenian democracy, emblematic of a wider collapse in the Classical civic ideal.

The story then turns north to Macedon, where Philip II, patient and ruthless, rebuilds power brick by brick. His victories do more than defeat city-states; they reorder the Greek world. The establishment of the Corinthian League creates the institutional framework Philip hands to his son, Alexander. Alexander's meteoric ascent forces defenders of the old polis—above all the orator Demosthenes—into renewed, desperate resistance, a final campaign of rhetoric and coalition-building that can't halt the tide. These chapters trace how stubborn local loyalties, soaring oratory, and a longing for a vanished past collided with the hard realities of a new political order.

The book closes with Alexander the Great, the fading of Classical Greece, and the rise of the Hellenistic world. Greek culture now radiates farther than it ever had, but political control fractures in unexpected ways: the great experiment of city-state politics gives way to sprawling Hellenistic monarchies, and local customs blend with Greek forms. What remains is not a neat, triumphant ending but a transformed world — a shifting tapestry of ideas, institutions, and art that spans continents.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789190150146

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 29/01/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.