- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

- Afhalen na 1 uur in een winkel met voorraad

- Gratis thuislevering in België vanaf € 30

- Ruim aanbod met 7 miljoen producten

Omschrijving

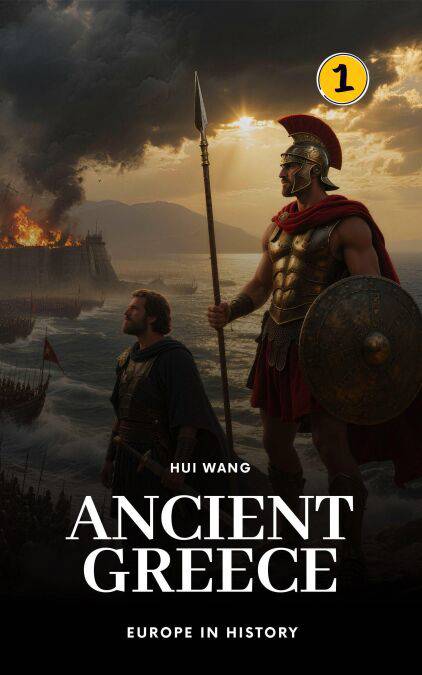

Ancient Greece: Europe in History, PART ONE, is the book I wrote to chase one question that kept bothering me: where did Europe really start to take shape? Not Europe as a modern idea, but Europe as a lived experience — a mosaic of places, practices, and habits people actually inhabited and remembered.

The story opens before written records, threads through prehistory, and finally steps into documented history with Minoan Crete and the Mycenaeans of the Bronze Age. From the labyrinthine halls of Knossos to the fortified citadels of Mycenae, I trace the slow emergence of a civilization — its palaces and fleets, its trade routes and raids — that would leave a deep imprint on the world to come. (For context: the palatial cultures I follow flourish in the broad span of the second millennium BCE, with Linear B tablets offering some of our earliest written glimpses.)

From there the book walks into the Greek Dark Age, that shadowed stretch after the collapse of the palatial world — roughly c. 1100–800 BCE — when cities and palace economies broke down, populations shrank, and the use of Linear B script ceased for a time. Out of that rupture came something new and slow-forming: the polis. Over the following centuries, small communities learned to govern themselves, to organize defense on a local scale, and to eke out livelihoods from limited land. In these conditions freedom, self-sufficiency, and rivalry found fertile ground. The so-called Archaic "revolution" — the political, social, and economic transformations of the Archaic period (about the 8th–6th centuries BCE) — altered everyday life, reshaped patterns of power, and sent Greek society down twin paths of intense competition and remarkable creativity.

Athens becomes the main stage for many of these struggles. I trace the rise of the Athenian aristocracy and the crises that followed—how debt, legal chaos, and widening inequality tore at the city's fabric. Figures like Draco and Solon step into that breach: Draco's famously harsh laws and Solon's later, more temperate reforms both matter; as important as what they changed is what they failed to fix. The narrative moves on through the age of Pisistratus's tyranny, the eventual overthrow of the Peisistratid clan, and the decisive moment when Cleisthenes shattered the old order and rebuilt Athenian politics in a bold, new key.

No Greek story stands alone, so the book turns east to Persia. I follow the rise of the Persian Empire and the first great collision between Persian expansion and the Greek world—the shocks that began with unrest in the Ionian cities and spilled into the wider Persian Wars. Those early encounters exposed just how fragile many Greek city‑states were when faced with a vast imperial power. Sparta enters the story through the figure of Lycurgus—traditionally credited with forging its austere, disciplined way of life, a portrait that carries myth as well as history. Athens answers in a different register, investing in a fleet and binding its fortunes to the sea, a strategic turn that reshapes its destiny.

Everything comes to a head in the Second Persian invasion of Greece. Leonidas makes his stand at Thermopylae; Themistocles stakes everything on the ships at Salamis. City-states argue, hesitate, and cast votes and votes of confidence that amount to nothing less than survival or annihilation.

Specificaties

Betrokkenen

- Auteur(s):

- Uitgeverij:

Inhoud

- Taal:

- Engels

- Reeks:

Eigenschappen

- Productcode (EAN):

- 9789190150122

- Verschijningsdatum:

- 27/01/2026

- Uitvoering:

- E-book

- Formaat:

- ePub

Alleen bij Standaard Boekhandel

Beoordelingen

We publiceren alleen reviews die voldoen aan de voorwaarden voor reviews. Bekijk onze voorwaarden voor reviews.